How to master your first foreign language

How to master your first foreign language

An accepted truth in the language learning community is that “the first language is always the hardest” – after that, each new language becomes progressively easier.

But why is this?

Is it because your brain becomes better at absorbing new words and grammar in the same way that a muscle becomes stronger through use?

While there is an element of this, it’s not the main reason. It’s because, through trial and error, over time you learn what works and what does not.

With experience, you come to know which techniques are useful and which ones are a waste of time; you learn how to learn a foreign language.

There is a common misconception that to excel in languages, you need a special talent.

While it is undoubtedly true that some people are better at it than others – for example, having a good memory will certainly help – the good news is that anyone can learn a foreign language if they know the right way to do it.

And to help, in this post, I’m going to start letting you in on some the “secrets” to mastering a foreign language.

How do babies learn?

Traditional language teaching focused on learning grammar rules by heart and reciting lists of vocabulary.

This is still many people’s idea of learning a language.

However, this is not the way we learn a language!

If people were successful, it was despite the teaching method rather than because of it.

Modern techniques focus much more on acquiring a new language in the same way that we learn our first.

This brings me to my point.

So how do babies learn?

Babies don’t replicate speech in the first six months of their lives, but they are attentively listening.

Within three months, they realize the sounds they hear hold meaning, and at six months, they begin vocalizing and trying to imitate those sounds.

Between six months and a year, they start to distinguish between certain sounds, and after the first year, real understanding begins.

This is still very much the passive stage, and they still can’t make words of their own – but they are constantly exposed to lots of language input, and they never stop listening and absorbing.

Gradually, as they approach 18 months and then two years, the passive phase of learning becomes active, and they start to experiment with words of their own.

They combine words into sentences, and soon after, they are able to express an ever-expanding range of ideas.

Modern language learning techniques

Modern teaching techniques try to replicate the natural way babies acquire language.

This means the first stage is the input phase where you are exposed to the new language.

The next step is practicing the language yourself by repeating it, like a baby experimenting with new sounds.

Finally, you need to be able to produce it in a real environment, which is when the new language is consolidated and becomes fixed in your long-term memory.

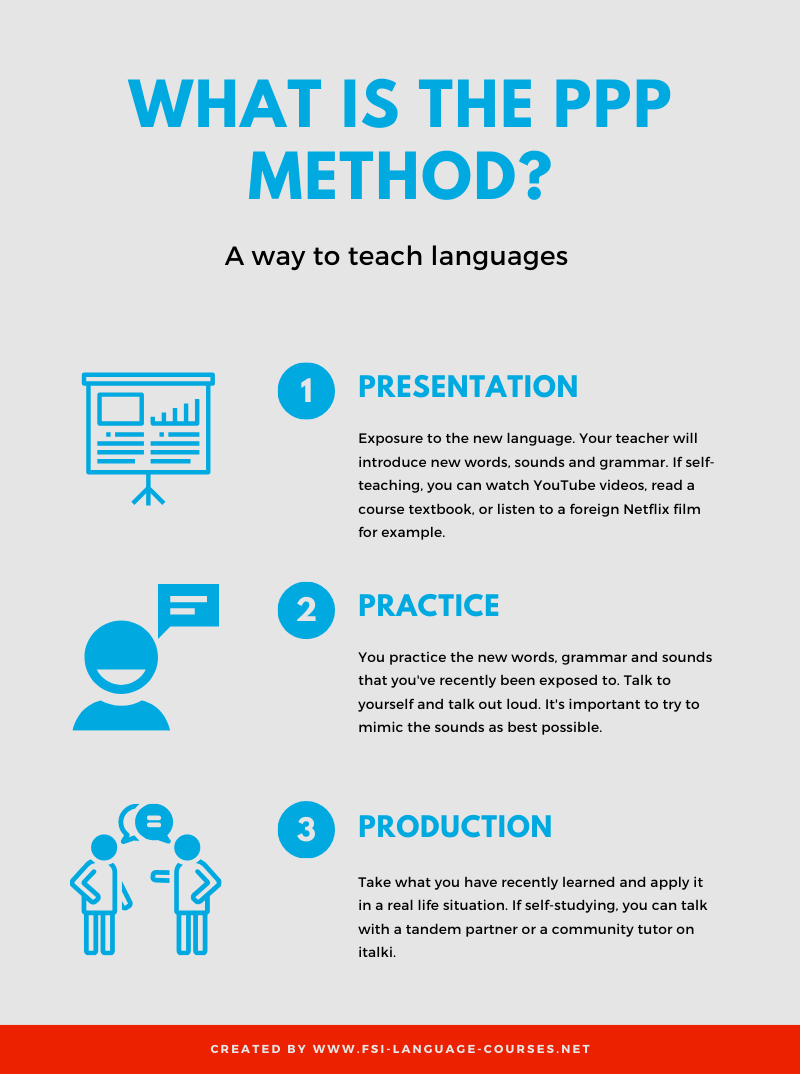

This is the PPP method of language teaching – which stands for Presentation, Practice, Production.

This method has its critics but it is popular and widely in use today. It is known to be highly effective.

How is this relevant to you?

Contrast this with the old-fashioned methods of teaching.

When you learned your native language, you didn’t learn it by memorizing lists of vocabulary or having grammar rules explained to you by your parents.

In fact, unless you learn another language or become a language teacher, you will probably be unaware of much of the grammar you use in your daily life.

Can you explain when to use “I did” and when to use “I have done”, for example? Unless you teach English as a foreign language, this is probably quite challenging!

We don’t learn languages like this as babies, and we shouldn’t learn foreign languages like this as adults. We learn languages through input, experimentation, and practice.

To put it another way, it’s a bit like learning to play tennis. You don’t do it by having someone explain the game to you; you learn to play by watching other people and then picking up a racket and having a go yourself.

This is what you need to do when you learn a language, too!

So how should I learn?

The first thing you need is “input”. For this, you need a good language program.

FSI courses, Assimil, Pimsleur - they will all present to you the new language, giving you lots of examples of how it is used in real situations.

You will hear the words being spoken from recordings and you should try to repeat them.

Just like a baby, at this stage, you won’t be able to have a conversation.

But…

you should begin by familiarizing yourself with the sounds and patterns of the new language.

Try reproducing the words and phrases you hear and try to imitate the pronunciation as best as you can.

However, you’re not a baby, and you don’t need to wait two years before you can start speaking!

As adults, we have many advantages over babies. From the beginning, you can start using the new language.

You can begin manipulating the new words in sentences and trying them out. Speak out loud to yourself.

Use a range of materials – and practice

One of the keys to success is having access to a range of materials.

Ensure you see the language being used in as many contexts as possible. This is especially important if you are learning alone.

At the same time, you need to practice what you learn as much as possible so it becomes second nature.

For example, let’s imagine you’re learning French.

In French, if I give you:

- 10 fruits (apples, pears, oranges...)

- The numbers 1 to 10 (un, deux, trois...)

Then ask you how to say “how much is a kilo of…?”, you should be able to say “how much are three kilos of apples?”.

You now possess the knowledge.

But...!

You haven’t practiced the language enough.

So when situation occurs in real life, you’re likely going to freeze and/or stumble over your words. It’s going to take you a few moments to produce a sentence.

This is because you are constructing the sentence word by word in your head beforehand.

But this isn’t how we speak our native language. It isn’t how we should learn to speak foreign languages, either.

Our goal is to be able to produce sentences fluently and without thinking, whenever the situation arises.

For this, we need to make use of different materials that expose us to the language being used in a variety of situations while giving us plenty of chance to practice and build that fluency – and this is why the FSI courses are so useful.

FSI Basic courses, in particular, contain a wealth of audio input.

They also provide you with countless drills to allow you to practice manipulating the language in a structured way.

So, with sufficient practice, when arriving at that French market, you will effortlessly be able to produce the correct sentence. Be it with apples, oranges or peaches, and in whatever quantity you wish.

To draw upon our tennis analogy, FSI drills and language practice is spending an afternoon working on your forehand. That forehand will then come to you without effortlessly in a real match.

What about grammar?

So how do we learn grammar?

Don’t we need grammar to speak correctly?

No but....yes.

A book on how to operate a car will do nothing for you learning to drive. The same goes for rules of the road, it won’t make you a competent and safe driver.

Driving is a skill and comes through practice and experience - not through theory alone.

With language, grammar is like the car operator book, but just as you can drive a car without knowing all the internals, so you can speak a language without knowing the intricacies of its grammar.

That’s how you learned your own language, and that’s how you should learn a foreign language, too.

So we don’t need to learn grammar?

I’m not saying grammar is not useful.

You need to know some grammar to form a correct sentence. But learning grammar from a book will not make you a good speaker alone.

You learn grammar naturally through practice and exposure.

You might know a grammar rule, but if you consciously think of it when you’re speaking, you’re not doing it right.

You need to learn to speak correctly without thinking about it.

When you master a foreign language, there are many grammar rules you are not even aware you are following.

Just like in your native language, you learn to speak correctly without studying the rules.

To master a language, stop asking why and just to ask how.

You don’t need to know why something is said a certain way, you just need to know how to say it.

This is a much more effective way to approach grammar.

Being able to accept this will make learning languages much easier for you.

Practice often and seek out opportunities

We have covered learning new material - “Presentation”.

You have your drills - “Practice”

But what about “Produce”?

Produce - seek opportunities to naturally use what you have recently learned.

You need many opportunities to use the language “in the wild”. Be brave.

When I was first living in Brazil, I was relentless with this. I would spend the morning studying, and then use the rest of the day to practice.

I would approach people in the street if only to ask for the time (I already knew the time). It would create a conversation. I wouldn’t understand much of anything, but that constant exposure accelerated my learning.

You too should seek these opportunities. Fortunately, this is easier now than ever before with the likes of meetups like mundo lingo and online lessons with platforms like italki.

Both of those are great ways to practice – and here’s another tip, you don’t necessarily have to practice with a native speaker (my italki German tutor was Portuguese for example, and she was excellent for understanding the rules of German).

However, nowadays, many apps exist specifically to connect you with other language learners around the world.

If you want to practice Chinese, it’s now easy to find a language partner in China.

You can speak to them every day through various platforms.

You can type messages, you can send audio or you can even do video calls.

Learning a language has never been as convenient or practical as it is now.

In any case, try to make your new language a part of your daily life. Try to find ways of using the language every day rather than just studying it.

Be creative

To start having conversations in a foreign language, you need to reach a certain level.

But…

There’s still plenty you can do before you arrive at that point.

You can start by talking to yourself in the language you are learning.

...or talk to your dog.

This might sound strange or crazy, but it can really help.

I once heard a story of a student in China who was learning English. His spoken English was far better than any of his classmates, so his teacher asked him what he was doing to improve – and his answer was astonishing.

He said that each night, he would put on the TV in English and pretend that the people were talking to him – and each time they spoke, he would answer in English.

Again, this sounds a bit unhinged, but evidently, it worked because his spoken English was so good.

Experienced language learners know how to be creative and can come up with new ways to learn.

In the introduction to the FSI Basic Turkish course, there is a line that stands out.

It says, “nobody can teach you Turkish, you have to learn it” – and this is true of any language.

You can’t rely on books or your teacher.

You have to take control of your own learning, get out there and improve.

The final piece of the jigsaw

I discussed with you that you need lots of input from a wide range of sources.

You need to be able to practice that language.

You need to produce and use the language in the real world.

But there’s one more vital piece of the jigsaw that will allow you to master your first language.

I always say to people that no language is difficult if you study every day.

But even the so-called “easy” languages become almost impossible if you only study once a week.

It’s much better to study for 30 minutes every evening than to study for four hours every Sunday afternoon.

Language proficiency comes through regular practice and through using the language every day. I talk about this in a follow-up article.

If you can find the time for half an hour or 45 minutes of study each day, even if you are trying to learn something “difficult” like Japanese, Chinese or Arabic, you will make rapid progress.

However, if you pack all your study into one intensive session once a week, it will be a long, hard slog, even with something relatively simple like French or Spanish.

Structured study

To bring everything together, you also need to be systematic about what you are learning and how you go about it.

You can be overwhelmed by everything if you’re inexperienced.

You might not know where to start. But choosing a good coursebook will give you the structure you need.

This should then be supplemented by any other resources you can find. Along with your main study materials, you can use podcasts, reading texts, learning apps and much more.

The FSI materials can play an important role in this, either as your main source of input or as a supplement to another course.

Many self-study language courses can provide the structure you need as well as examples that present new vocabulary or grammar.

However, few can match the sheer volume of material offered by the FSI Basic courses.

Using both together can be an excellent way to provide an abundance of language input and opportunities for the practice you require.

A general overview – but more to come

In this post, I have given you an overview of the best approach to language learning.

- You need plenty of input (course text and audio, podcasts, newspapers, YouTube, films).

- Lot’s of output (i.e. vocalize at home, in a class, with an italki teacher).

- And the most important - lots of practice in real situations (meetups, online-gaming, italki conversation partner).

In future articles, I will deep dive into the specific techniques you can use to accelerate your learning. You’ll find hacks to improve your vocabulary, fluency, and pronunciation.

How far into your language journey are you? Let me know in the comments below.